In northern Ontario’s isolated locations, where licensed subject teachers are often hard to find and high-speed internet connectivity may be as unpredictable as the weather, something quite imaginative is happening. In some faraway schools, AI co-teachers like Gemini have started to help teachers, not take their jobs, but stand by them.

It’s a nice, practical way of thinking. Teachers don’t have to give up control or change the way their classrooms look. They are getting help with lesson preparation, making engaging materials, and presenting material in a way that is tailored to each student. Because of this, many teachers say they have saved up to 10 hours a week, which they could have spent with their students.

Ontario AI Co-Teaching Pilot – Key Program Details

| Detail | Information |

|---|---|

| Program | AI Co-Teachers in Remote Northern Ontario Schools |

| Purpose | Support teachers, enhance learning, reduce admin time |

| Tools | Gemini and other generative AI systems |

| Teacher Time Saved | Approx. 10 hours per week |

| Focus Areas | Personalized tutoring, lesson planning, admin support |

| Pedagogical Approach | Human-led instruction with AI augmentation |

| Ethical Emphasis | Student digital literacy, responsible AI use |

| Reference |

In some communities, especially those with less than 100 students in multiple grades, one instructor often teaches many classes. This project gives you a very useful digital companion to help you do it. One minute, it might give you math problems with hints, and the next minute, it can give you English reading comprehension activities. All with a few well-thought-out hints.

Schools are getting a lot of useful and different aid by using advanced language models, especially in places where professionals are alone every day. Teachers can now use more than just their free time after school to make differentiated resources. The AI’s ability to quickly change content has made it much less likely that I will have to stay up late rewording reading passages for hard readers or making worksheets.

Professional development is also a top emphasis, along with deployment. Jamie Mitchell and Tamara Phillips, two teachers who are early supporters, are examples of early supporters. Mitchell, a math expert, said that teachers need AI advice “without a doubt.” Phillips, an English teacher, underlined how important it is to avoid binary thinking, which sees AI as either beneficial or bad. She says that the hard part is understanding the tool and using it to reach educational goals.

The initiative has some problems. Important challenges include accessibility, student data, and the subtle pressure that AI tools may put on teachers to produce “output” more quickly. But the people who made the program have taken a human-centered approach. The AI is not used to watch, punish, or grade students. It helps maintain the backend without drawing attention to itself, making things easier and freeing up people to teach more directly.

This change—from paperwork to presence—makes it especially useful in northern schools, where building trust is just as crucial as teaching. When teachers aren’t busy with paperwork, they have more time to mentor, think about things, and talk to students. Machines can’t do these things since they are human-emotional activities.

During an early visit to the school, a teacher asked Gemini to change a fractions lesson so that it was easier for a fifth-grade student with a learning difficulty to read. The technology made a clear, easy-to-read version in just a few seconds. But the real magic happened later when the student leaned over and asked the teacher, “Can this thing explain it in Oji-Cree?” The AI couldn’t do it. The teacher said softly after a pause, “Let’s find a way together.” That moment will stay with me forever. It showed how even the best-designed tools can be useful and how they might also be limited right now.

The rules for teaching AI are still not the same all over Canada. Most governments, including Ontario until recently, have just given generic advice. Alberta and Quebec, on the other hand, have given specific plans. British Columbia’s districts can make their own rules, and Newfoundland and Labrador has started training teachers (2,000 so far) to use these tools quickly.

A lot of money has been spent on digital literacy programs and edtech infrastructure, but very few places have tried what Ontario is doing right now: using AI alongside teachers in rural schools to solve real gaps in resources and people. Not as a flashy project, but as a well-planned support system.

People say that since the initiative started, students have been more interested in classes like math. Because of the AI’s interactive learning ideas and 24-hour coaching options, students are asking more difficult questions and staying interested for longer. It’s more vital to spark curiosity than just automate processes.

Most importantly, kids are also learning how to utilize AI responsibly. Ethics are very important and should not be ignored. The goal is to teach students how to check their results and spot bias, as well as how to develop the kind of skepticism and digital discernment that modern citizenship needs. In this case, the classroom becomes a lab where thinking is improved instead of replaced.

The ministry of education is keeping a close eye on how the pilot is doing. Feedback loops between legislators and schools make the implementation flexible. If this idea works, it might be a major strategy for other provinces and territories that are having trouble hiring people and have regional imbalance, not only Ontario.

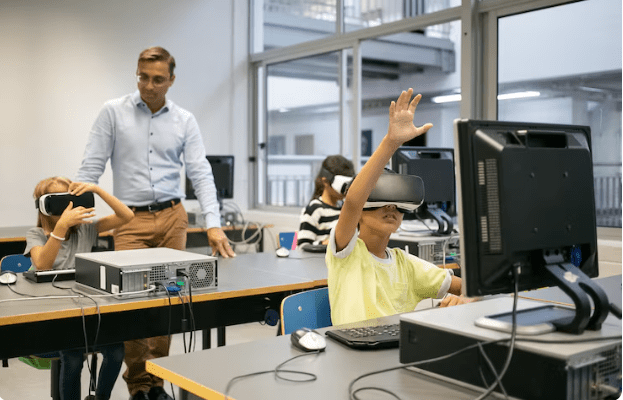

Ontario’s decision to test AI as a co-teacher in the classroom is a sign of a bigger shift in how new ideas are being used in education. There are other things to do besides bringing devices into the room. It means setting up interactions between people and machines so that teachers can use their brains and hearts to lead while being helped by very reliable tools that do boring, repetitive tasks.