The worldwide competition to construct the vertical city with the fastest rate of growth is an astounding demonstration of technological prowess and human ambition. Countries are rethinking what cities can be—dense, effective, and vertically alive—across deserts and river valleys. The Line, a 170-kilometer-long linear city rising in the NEOM region of Saudi Arabia, is at the forefront. It seeks to run entirely on renewable energy, doing away with cars and streets entirely, and is envisioned as a glass-walled home for nine million people.

The Line promises a radically different lifestyle by utilizing prefabricated modules and AI-driven urban design, with every home, workplace, and school all within five minutes’ walk. By converting the desert into a networked ecosystem of vertical living, the project ushers in a new era in city planning. It is “a revolution in urban design,” according to Saudi leaders, where people and nature live side by side in harmonious harmony.

| Aspect | Information |

|---|---|

| Leading Projects | The Line (Saudi Arabia), Sky City One (China), Bride of the Gulf (Iraq), Chongqing Vertical Metropolis (China) |

| Objective | To build dense, sustainable, self-contained vertical urban ecosystems |

| Architectural Vision | Car-free, renewable, AI-managed environments integrated with nature |

| Key Developers | NEOM (Saudi Arabia), Broad Sustainable Building (China), AMBS Architects (Iraq) |

| Engineering Features | Prefabricated modules, vertical zoning, and digital design precision |

| Societal Goal | Reduce sprawl, improve sustainability, and redefine urban livability |

| Global Competitors | Saudi Arabia, China, Iraq, and Southeast Asian cities |

| Reference | The Line Project – Discovery UK |

However, the East poses a serious threat to this goal. China, which has long been known for its intense architecture, has already shown how construction can be redefined by speed and accuracy. Prefabrication could completely alter the rules, as demonstrated by Changsha’s incredible Mini Sky City, a 57-story skyscraper that was put together in just 19 days. The fact that each floor was constructed using factory-made parts that fit together like a puzzle shows how technology can reduce years of work to a matter of weeks.

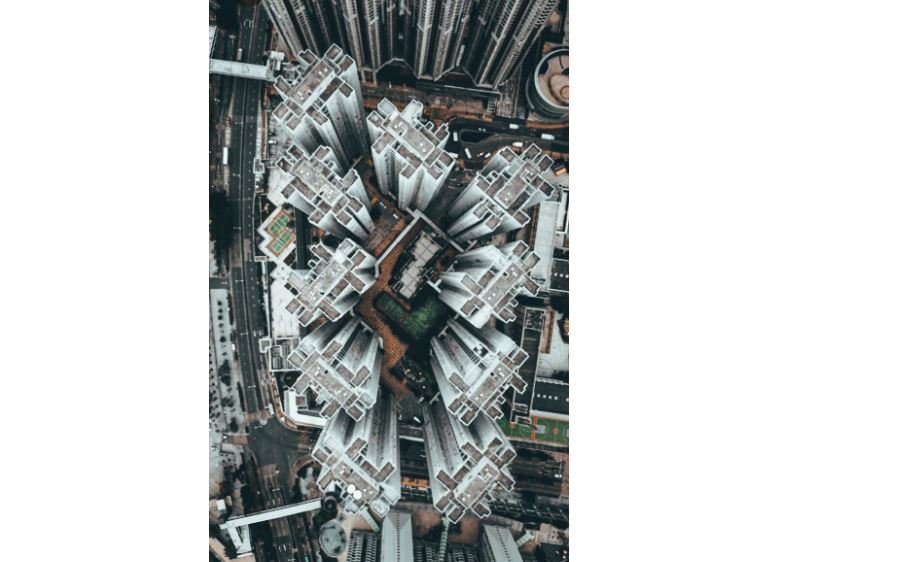

The mountainous megacity of Chongqing, China, offers yet another example of vertical complexity. In layers of steel and concrete, its design ascends steep cliffs and deep valleys at the confluence of the Jialing and Yangtze Rivers. In Chongqing, buildings frequently have more than one “ground floor,” with the first floor having a street entrance and the twelfth floor having another. Its light rail famously runs straight through a residential tower, illustrating the literal blending of everyday life and infrastructure. The way vertical living adjusts to geography, necessity, and innovation is embodied in this “8D” cityscape.

Iraq’s Bride of the Gulf project aims to restore architectural splendor in the center of Basra, far from Asia’s busy centers. It was designed by AMBS Architects with the goal of constructing a city inside a tower by rising more than 3,700 feet, or almost a kilometer, high. It would be an energy-independent building with sky gardens, vertical rail systems, offices, schools, and public plazas interwoven. According to the architects, it is “a city conceived to live both vertically and horizontally,” a sophisticated solution to the area’s declining land resources and expanding population.

The quest for height has changed from being a symbolic race to a mission motivated by sustainability across continents. China currently holds the top spot with over 3,500 skyscrapers taller than 150 meters, according to the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. While cities like Bangkok and Manila are expanding upward to accommodate growing populations, Southeast Asia’s skylines are being redefined by Malaysia’s Merdeka 118 and Indonesia’s Thamrin Nine. Skyscrapers have evolved into vertical symbols of progress for many countries, signifying technological advancement and economic confidence.

Despite its ongoing development, Saudi Arabia’s The Line represents a previously unheard-of vision for human existence. The goal is to build differently, not just upward, by developing AI-powered vertical neighborhoods that foresee needs before they materialize. In just a few minutes, high-speed trains will connect communities as they pass through its center. Real-time power demands and solar and wind inputs will be balanced by renewable grids managed by predictive algorithms. It is an autonomous urban organism that serves as a living test bed for cities of the future.

On the other hand, China’s abandoned Sky City One continues to serve as a warning about ambition reaching its limits. The Changsha project, which was supposed to reach 838 meters, was shelved due to safety, environmental, and regulatory issues. But its legacy lives on. Its innovative modular construction methods have become widely used, impacting the design of infrastructure, hospitals, and homes. These techniques have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in reducing waste and time, especially in emergency construction situations where every minute counts.

Meanwhile, Chongqing’s multi-tiered transit systems and suspended bridges continue to astound engineers. For planners dealing with space constraints, its vertical zoning logic—where homes, schools, and public parks occupy different levels—has become a study model. The city shows how density, when properly planned, can improve rather than degrade quality of life by turning natural barriers into architectural assets.

The vertical city movement poses more profound social and environmental issues than just engineering wonders. Can neighborhoods prosper without conventional streets? Will management powered by AI feel liberating or invasive? If constructed as planned, these cities could significantly cut emissions, shorten commutes, and free up land for reforestation and agriculture. However, they must also guarantee inclusivity to keep futuristic skylines from turning into solitary bastions of privilege.

These projects have equally strong economic justifications. By promoting architecture as a representation of the country’s rebirth, NEOM supports Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 strategy to diversify away from its reliance on oil. China’s ongoing push for urban modernization and industrial innovation is reflected in the growth of skyscrapers. The Bride of the Gulf represents rebirth even in Iraq, turning a formerly war-torn area into a center of sustainable ambition.

The common factor driving this rise is still technology. These initiatives are developing into extremely effective ecosystems by combining data analytics, drones, and AI-driven systems. While 3D modeling software models airflow, light diffusion, and energy efficiency decades from now, robotic machines now manage modular assembly with astounding accuracy. The evolution of architecture from static to dynamic and self-regulating is remarkably precise.

An emotional truth is also tapped into by the fascination with vertical cities: people have always looked up for advancement. From the Burj Khalifa to Babel, height has represented perseverance, creativity, and hope. However, this new race is more about striking a balance—between ambition and empathy, expansion and sustainability—than it is about defying gravity. Saudi Arabia or possibly China may be the first country to build a vertical city with the fastest rate of growth, but its greatest success will be determined by meaning rather than meters.

One thing is clear as cranes pierce the sky and mirrored buildings reflect the desert sun: tomorrow’s skyline will support the clouds rather than merely scrape them. Today’s rising cities are designed to share the earth more thoughtfully rather than to control it. Additionally, humanity may finally be learning how to build toward harmony rather than height as a result of this upward march of progress.