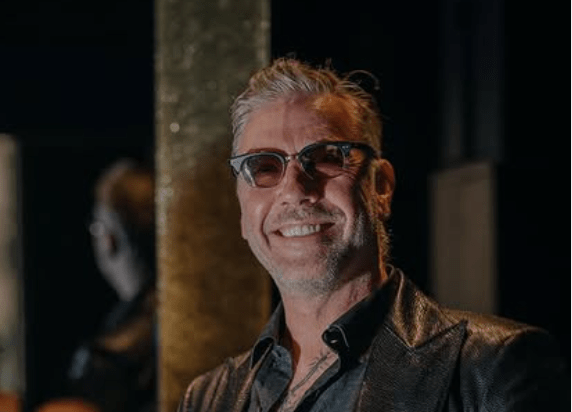

Cameras appear to be drawn to Mikael Persbrandt’s face because of its quietness. The energy stays, coiled, and waiting without feeling forced. Scandinavian fans have grown quite accustomed to that expression over the years, especially in his pivotal role as Gunvald Larsson in the Beck series. The sharp-edged voice, the tension, and the stare were more than just character traits. They were incorporated into his public architecture.

Before entering the commercial spotlight, Persbrandt, who was born in Jakobsberg, just north of Stockholm, rose to prominence in theater. He started honing his craft on stage in 1984 after being captivated by timeless plays like Death of a Salesman and King Lear. Even at that time, he was clearly different—volatile, physically intimidating, and emotionally erratic. These traits caused division among colleagues but also made him especially believable in the tragic roles.

Mikael Persbrandt – Key Facts

| Name | Mikael Åke Persbrandt |

|---|---|

| Date of Birth | 25 September 1963 |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Known For | “Beck” series, “The Hobbit,” “In a Better World” |

| Estimated Net Worth | $5 million |

| Major Awards | 3x Guldbagge Award (Best Actor), Ingmar Bergman Award |

| Notable Roles | Gunvald Larsson, Beorn, Carl Hamilton |

| Partner | Sanna Lundell |

| Children | 3 |

| External Reference |

His move from theater to film during the late 1990s was more than just a change of vocation. It signaled some sort of shedding. A strong outcry followed his departure from the Royal Dramatic Theatre; renowned Swedish theater critic Jan Malmsjö publicly accused him of treason. The phrase “he has pissed on us” was more about identification than manners. The decision was viewed as sacrificing artistic integrity for publicity in Sweden’s close-knit performing community. Nevertheless, the crowds followed him.

The risk was justified by what happened afterward. His portrayal of Carl Hamilton, Sweden’s version of James Bond, revealed a chilly accuracy that stood in stark contrast to his gruff physique. Not only was he convincing in the part, but he was also incredibly successful. He later softened a little in Susanne Bier’s In a Better World, when he played a physician torn between trauma and recovery. He received a nomination for a European Film Award for the performance, which also made him more widely known.

Persbrandt joined the Tolkien family through Beorn, the shape-shifting creature from The Hobbit trilogy. Even though he didn’t have much screen time, it seemed culturally fitting to cast a Scandinavian actor in the part. The manner that he depicted controlled aggression—half myth, half man—was especially inventive. It gave him a signature that went beyond Sweden’s boundaries, but it didn’t make him a worldwide celebrity.

The financial benefits reflected the trajectory of a career that was first developed slowly and subsequently profitably. Even though his estimated net worth is $5 million, his tale is not told by the headline numbers. He never pursued endorsement deals or big-budget franchises. His income, which was remarkably steady, came from making a lot of movies, each one chosen with an instinct that felt more instinctive than calculated.

Persbrandt increased his artistic legitimacy by working on Nobody Owns Me with filmmakers like Björn Runge. He received his second Guldbagge Award for his unvarnished and agonizing performance. Without being stylized, the part revealed addiction, guilt, and redemption. It was like watching a man peel back the layers he had once used to protect himself as he moved through that movie.

However, there is a balance. His sometimes erratic private life reflects some of the mayhem he portrays on screen. It was well acknowledged that he had previously struggled with substance usage, but he seems to have centered himself more recently. His family home in southern Stockholm is said to be surrounded by nature, which may be a more tranquil environment for a man who has spent the majority of his artistic life under strain. He shares three children with journalist and singer Sanna Lundell.

Through roles in films like Sex Education, in which he portrayed Jakob Nyman, Persbrandt has maintained his prominence in recent years. The character, a friendly, practical Scandinavian handyman, seemed purposefully cast against type. The tenderness shocked viewers who only knew him as Gunvald. His grounded presence was simply welcomed by younger audiences who were not familiar with his previous career.

Aging into new parts is especially advantageous for actors like Persbrandt. They become stores of knowledge or enigma, letting go of the demand for control. The audience presumes his strength, therefore he no longer needs to demonstrate it.

His wealth isn’t what makes him a particularly interesting case study. His financial situation is modest when compared to Hollywood A-listers. But when compared to the relatively small, publicly supported Swedish film industry, his profits show a surprisingly successful career based on craft and persistence.

He’s not starting apparel brands or tech firms. He is acting, which is what performers used to do. That choice has paid dividends over the last ten years—not with jets or mansions, but with unexpected reinvention and artistic relevance.